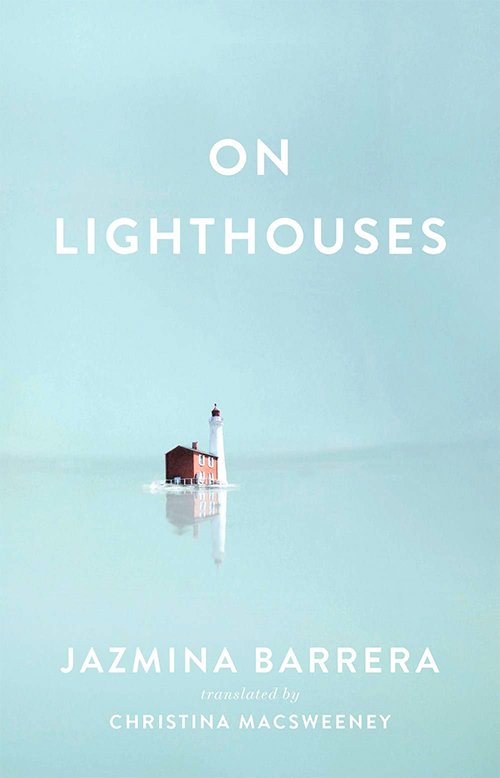

Katy: When I read On Lighthouses I was coming out of a strict, two-month lockdown here in Madrid. I felt like one of the lighthouse keepers described in the book—isolated, even on the verge of madness at times.

Jazmina: I like this idea that we’re all lighthouse keepers at the moment. Lighthouse keepers have to isolate themselves to take care of other people, what they´re doing is looking after people at sea. We’re also isolating ourselves to take care of those around us, even strangers. The book has had a strange relationship with readers during the pandemic. It talks a lot about solitude and many people have recommended it for these times.

Katy: There is also movement in the book, which contrasts with the static, stoic nature of lighthouses. You take us from the Oregon Coast to New York to rural France to Asturias. There’s an opportunity to escape the confines of home. How involved were you with this journey, Christina?

Christina: I was very involved with it, in that sense of travel. The moments I really loved were moments when Jazmina lets the light shine on her. You have these amazing stories around her, but there is pain and sorrow and worries. All those things are going on with the lighthouses, and that reflects on the experiences of lighthouse keepers—for example, their isolation and depression some of the time. That’s what I really liked about it, I felt I had been given an invitation into Jazmina’s life.

Katy: Ishmael, in Moby Dick, suggests that all men’s roads lead to water. At what point in your life were you drawn to water, specifically towards the act of collecting experiences around lighthouses?

Jazmina: It started with a trip I did to the coast of Oregon. I went with my family and we stayed at the Sylvia Beach Hotel, where the rooms were all decorated according to certain writers. There was a beautiful lighthouse near the hotel. I was also reading To the Lighthouse, so I wanted to write about the reading experience in combination with the travel experience.

Katy: I see that pattern play out throughout the book—the way you pair the reading and travel experiences and in traveling, how you literally collect places.

Jazmina: It’s true, I was traveling to lighthouses in Spain when I wrote the travel log at the end of the book. It’s interesting that the book starts with a dialogue between To The Lighthouse and the travel I was doing while reading it, and the book ends with this reading experience of the Sir Walter Scott book [Northern Lights: Or, a Voyage in the Lighthouse Yacht to Nova Zembla and the Lord Knows Where in the Summer of 1814] and the travel I was doing at that time.

Katy: It’s interesting that you write about Sir Walter Scott in the present tense and your own journey in the past tense because, as you write in the book, you feel “as if what happened to Scott so long ago is more present than what” you’re experiencing. How did you approach the integration of literary texts like this, Christina?

Christina: One of the things I had to think about was what to do with the literary sources that are used in the book, how to integrate them into the text in English. After you do this a few times, it’s a bit like Chinese whispers. Things don’t always match up from one language to the other. It was particularly true with the Sir Walter Scott part in the final section of the book. Sometimes he’s using quite archaic language in English, which isn’t really there in the Spanish. I thought, “I’ve got to look at these references, find the originals.” The world he’s describing isn’t that long ago really, but it just felt like a thousand years ago.

Katy: Do you enjoy this research element of your translation work?

Christina: Yes, and it was particularly fascinating to learn more about the technology of lighthouses. Sometimes, I was tearing my hair out, putting myself in a science position. But I quite loved the responsibility of getting the terminology right. I couldn’t just make it up and hope that readers wouldn’t notice. That was something that took me to a different area, which was a nice thing to do.

Katy: And how did your personal research influence the writing of your book, Jazmina?

Jazmina: I was initially doing research on lighthouses out of curiosity. I got obsessed, and I fell in love and started reading more about lighthouses and taking every advantage to visit other lighthouses. It began to build as this collection of experiences, travels, and books. I wanted it to be like a cabinet of curiosities. It was a visual process for me. I wanted the fragments to be like objects. Because collections are an important theme in the book, I wanted the whole book to be a kind of collection. I wanted the fragments to dialogue with each other, as the objects in a collection talk to each other, in a way.

Katy: You write that you’d like to rescue lighthouses from invisibility or keep some of their stories alive, as well as be guided by the objects themselves. How did you visualize your texts as objects in a collection?

Jazmina: I actually had a program called Scrivener. It has an option to play with Post-Its and move them around and put labels on them. You can have a board. I don’t know what I would have done without that. I was living in New York at the time, so I didn’t have the space to move physical objects around.

Katy: During your research and process of assembling texts, did you consult some of the log books of past lighthouse keepers? Did that inspire the log at the end of the book?

Jazmina: Yes, I did. Many of them are quite technical and talk about things like the weather, or times of day the lights were lit. Yet, with such scare information you can put together a story. A couple of books were very evocative for me: Robert Louis Stevenson’s book about his family of engineers, and the Sir Walter Scott book that he wrote when he was in a boat with Stevenson’s grandfather traveling to lighthouses around the Scottish coast. At the end of my book, I wanted the log to have a direct conversation with Scott’s book.

Katy: In a way, your book represents subjective motives in conversation with the external world. That idea that a journey is the externalization of an interior seeing. Was this intentional or accidental?

Jazmina: It became a question of the book: to what extent do we write about ourselves when we write about something else? And vice versa. There is, for example, the metaphor of the lighthouse as the travels, the external elements, stories, and I used the metaphor of the well to talk about introspection, the subjective and the personal. The book tries to combine those two discourses and to reflect on the differences between, say, the travel log and personal diary. What kinds of genres are they, and how do they relate to each other? I really enjoy those kinds of books, the ones that create a relationship between the subjective and the external and the rest of the world. I tried to do that and to talk about the necessity of escaping oneself and the impossibility of doing so at times.

Katy: How were you trying to escape exactly?

Jazmina: By placing my attention in nature, in other stories that were so appealing to me. The topics around the lighthouses that are so attractive: solitude, madness, the sea. What became rather obvious at one point was that all of that reflected, in a way, what I was feeling, so there was no escaping the place where I was. It finally got through in the book. In a way, it’s a very sad book. So I think that even though I wasn’t trying to write so much about myself, it became a book about myself at that point in my life.

Katy: Christina, when you were translating the book, was it difficult to convey the emotional resonance of the text? I suppose it’s easier to translate facts than emotions.

Christina: I’m not sure translating factual information is any easier. When you go deeper and deeper into the text, to some extent, you are sharing the emotions.

Katy: How did you get at the rhythm of the text?

Christina: I’m not 100% sure. Some people have an ear for music and can pick up a tune very easily. I seem to have an ear for music in a text. Maybe it’s the way my mind works, or the way I read. I’m truly reading with that music, that rhythm. Maybe it’s one of those things you’re born with. You’re sort of dancing to the text when you’re translating—with your fingers.

Katy: I suppose the tone emerges as the text takes on rhythm?

Christina: The tone, I think that comes about itself. It develops. Translation is like stepping into someone else’s shoes and walking around in them. Once you do, the tone becomes natural to you to some extent. Then you go to some other project, and the tone is all wrong. But the tone in the translation can never be exactly the same as in the original.

Jazmina: Yes, and every language is also a tone in itself.

Katy: Did the English version become its own entity apart from you, in some way?

Jazmina: It’s wonderful for me to read the English version. It’s like reading a book I really like, written by someone I have a lot in common with, but that is still new. The words feel fresh. It’s a very different entity. I love the feeling of reading the translation.

Christina: The translation allows the authors to stand back a little bit, to put some distance between themselves and their work.

Katy: Jhumpa Lahiri’s bilingual memoir, In Other Words, reveals that she feels freer writing in Italian than in her native Bengali or in English. Is there a language in which you feel more free?

Jazmina: I don’t think it works that way for me. I studied English literature, and although I love it, I never felt I had as many tools as I needed to be able to write creatively in it. Beckett said something about saying what you need to say in fewer words. That’s an interesting challenge as well.

Christina: There are some things I find much easier to talk about in Spanish than in English. Sometimes Spanish molds itself to what I want to say more easily.

Jazmina: Yes, and it happened to me a lot in New York, where I found myself thinking things in English, things I was living in English. It’s an interesting thing to think about. I don’t know if there are things that are easier for me to think about in English, but I suppose there must be.

Katy: What was it like working closely with a translator, watching your text evolve into a slightly different version of itself?

Jazmina: First, I have a friendship with Christina so there was a lot of interaction in every sense. More communion and communication.

Christina: After we met at a book launch in New York years ago, I thought, “This is somebody I like, this is somebody I want to read.”

Jazmina: Oh, thank you! Every translator has a different style, and you really engage with the text, Christina. I remember you sending me questions and problems related to the text, but you always suggested such wonderful solutions. I think, in a way, it’s a better book in English than in Spanish because it has an extra layer of work. I’ve taken notes of everything so when the Spanish version gets reprinted I can use what we did to make that version better.

Katy: I’m glad to hear the book will be reprinted soon. How has the reception been overall?

Jazmina: I really liked the experience of being published in small presses around the world. Next year it will be published in Argentina, in Italian, in Dutch. The excitement of the editors is palpable, and it translates into the excitement of the audience. This energy speaks to how lighthouses are a universal symbol.

Katy: To quote the book, “A controlled flame is an indication of human presence; their message is, first and foremost, that human beings are here.”

Jazmina: Yes! Even if people don’t have the literal building of the lighthouse, many people use fire in ways that work as lighthouses for fishermen in coastal towns. People everywhere relate to this book in one way or another. The English translation was a bittersweet experience because it started with so much excitement, and we had so many plans for the book tour in the US this year.

Christina: It was great to see how people engaged with the book. At Two Lines Press, our editor was initially uncertain about publishing it, but he said, after a while, that he couldn’t get it out of his mind; that it was there all the time. This is the effect it has had on many people.

Katy: Will you write more about lighthouses in the future?

Jazmina: It’s a book I could have kept writing forever because it has such a free structure, you could keep traveling to lighthouses. There are so many of them, and each one is like a house of stories. So it’s an infinite book that I decided to abandon at a certain time, because I wanted to write other things, not because it wasn’t interesting for me anymore.

Katy: Lighthouses are constantly personified in your book. You describe it as the guardian of the sea, a constant watchman, a “living and intelligent person.” So, out of all the lighthouses you’ve “met,” which one has been your favorite?

Christina: My family is Irish and we spent every summer on the southwest coast. One year, when I was about 8 or 9, we rented a cottage in the coastal town on Ballybunion. I shared an attic room with my sisters. On our first or second night in the cottage, I climbed onto a chair to look out to sea through the dormer window. What I saw was a strange light flashing on and off in the distance: I watched for a long time and convinced myself that the light was in fact due to pirate activity. The next morning, all excitement, I reported to my parents that there were pirates in Ballybunion and maybe we needed to tell someone. They laughed. That day we drove to Loop Head, across the estuary of the Shannon. My pirates were a lighthouse.

Jazmina: That’s a beautiful memory, Christina. You should write it!

Christina: You write it, and I’ll translate it.

Jazmina: My favorite lighthouse is not actually in the book; I went to visit it after I had finished the book. It’s a lighthouse off the southern coast of Chile. You have to take a boat to get to this island, where there’s only the lighthouse and a large colony of penguins. It’s such a wonderful place, a fairytale. I kept imagining living there and being the lighthouse keeper and having a relationship with these beings that are so human like, in a way, so strange and beautiful.