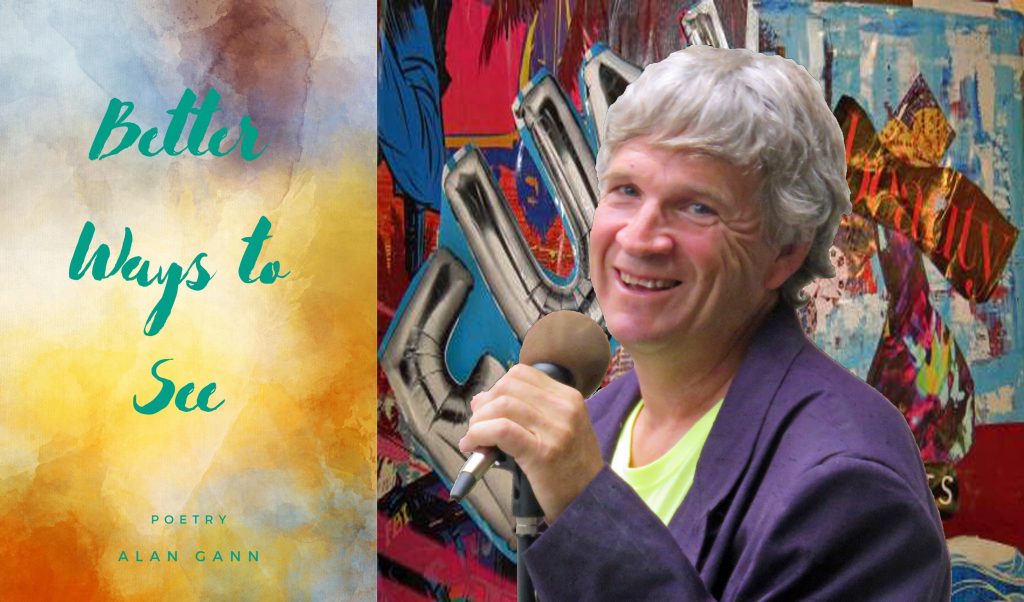

In Better Ways to See, Alan Gann offers us a fresh pair of eyes to catch the details we are likely to miss in the natural world. Every poem seems to ask, “why not sing or bloom or fly?” (“spiral orb”). Part I of this collection, “Wanderings with birds,” literally gave me the sensation of having wings, of believing “We each sing our morning notes/ to remind the world/ I’m still here and no matter/ what happens before night descends/ all contribute/ to the golden-holy-resplendent song divergent” (“Chorus”)

Nature overshadows human concerns. The senses are intermixed to the point of synesthesia—a fancy name for when you experience one of your senses through another. In the poem “Reverie,” the scent of fresh pine latches onto the crisp bite of a red apple. And even when the music fades, “we share a brief silence/ sacred as the unfolding leaf and three-quarter moon” (“Barred Owls”). The silence is given shape; it contains motion and emotion.

Absence of sound points to some other heightened energy as we see in part II of this collection, where Gann presents ekphrastic poems inspired by steel sculptures of the Storm King Art Center in the Hudson Valley, a locale that celebrates the landscapes that form part of the artworks themselves—the hills, meadows and forests. Only later, the narrator realizes this isn’t nature but instead a “crisp imitation” or art the perfection of nature (whereas part I of Gann’s collection seems to go with the Thomas Cole idea that nature is perfect art).

One poignant piece, “the poem I cannot write,” wonders “how many more names/ before I can write my poem/ how many more times/ will we have to cross that bridge.” The poem is based on the sculpture Fayette: For Charles and Medgar Evers, named for two brothers who were important figures of the civil rights movement, but Gann includes, in their memory, other Black lives lost.

Another poem, “Peach boy,” written about Isamu Noguchi’s Momo Taro, blends Japanese legend with the poet’s singing inside the aural chambers of a hollowed-out granite “peach pit.” We see the poet interacting with sculptures in a way that brings up memory; he recalls how his mom encourages him to crawl inside the sculpture, although she refuses to join him.

Gann’s collection ends the way it begins: with family. As the poet reflects on the loss of his parents, he reminisces on his and his mom’s last visit to the Storm King Art Center. He eventually returns to sprinkle some of his mother’s ashes around Noguchi’s stones. We find a permanency in art that is lacking in the natural world. The sculpture “Five Open Squares Gyratory Gyratory” by George Rickey, shows that landscape itself is always shifting, “the universe continues to bend” (“post Newtonian”). We move along with it. “What better thing than to wander and be astonished?” (“One possible answer”) These words speak for the entire collection. They speak of a way one could approach life, or an outdoor museum under open sky, or even a collection of poems.

Podcast episode

Book