Katy: In your book, collecting intertwines with storytelling. You share a quote by Valdís Einarsdóttir who said, “Why have a museum if you don’t have a story?”

Kendra: Icelanders are storytellers. For much of its history, this culture has been funneling many of its creative and intellectual resources into language. As a book built on oral tradition and the interview, the sound of it is something I value. Getting to record the audio book was the most fun I’ve ever had.

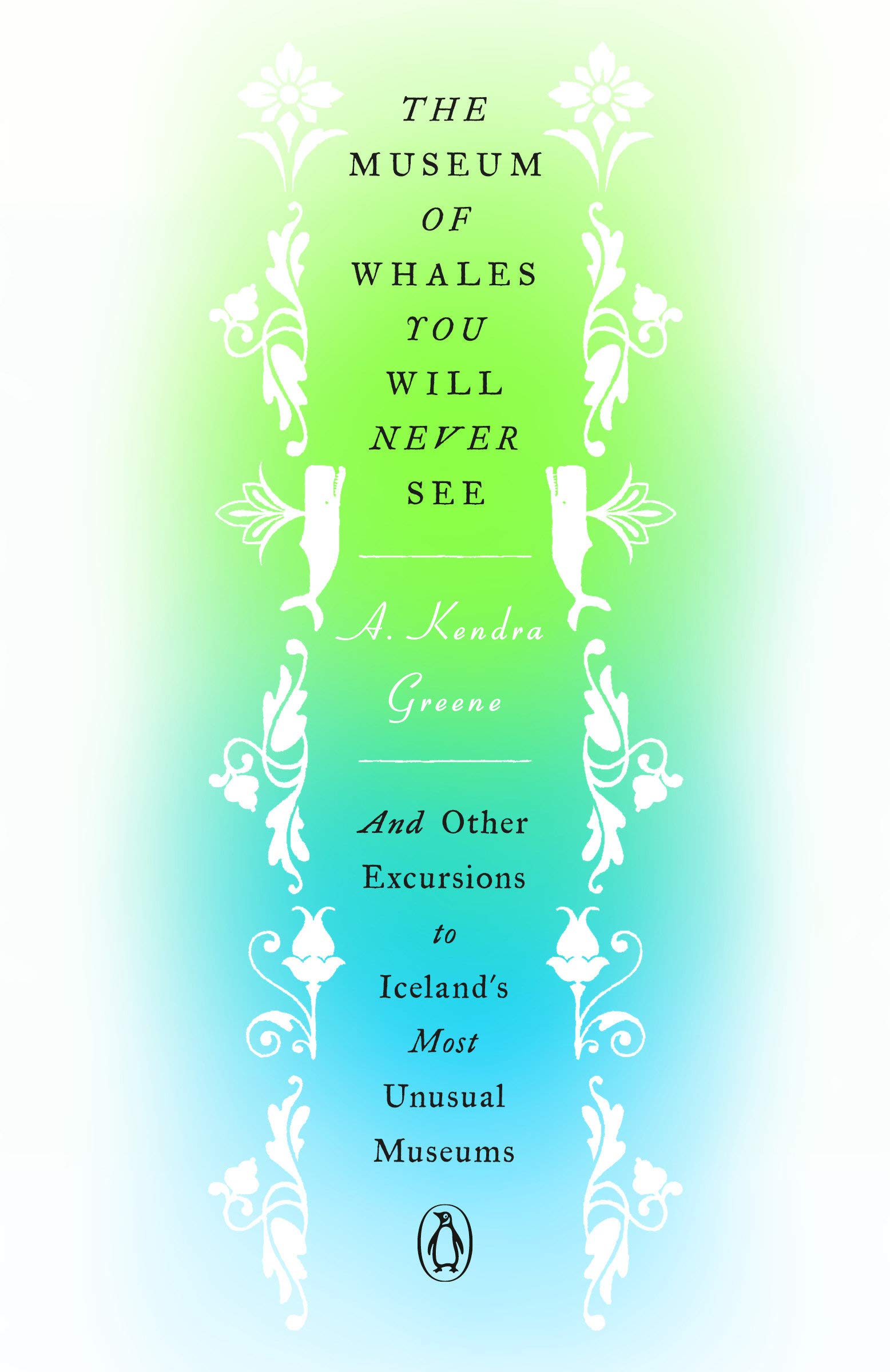

I’m so thankful to everyone at Penguin who understood it was a book emphatically about how an object tells stories, how literature fits at this crux—smoothed and polished over time.

Katy: That metaphor reminds me of Petra’s stone collection. I can see that Icelanders attach great value to real and imagined objects and bodies found in the natural world: birds, stones, polar bears, whales, herring, sea monsters, ghosts, elves, trolls. There even exists a collection of phallic specimens belonging to all the various types of mammal found in a single country.

Why do Icelanders connect so strongly to nature and all that inhabits it?

Kendra: It’s so easy to be romantic about the Icelandic landscape, so immediate and beautiful. Iceland is a land that hasn’t had time to erode. It inhabits recent space geologically, spaces where you can see exactly where two tectonic plates have come up against each other. The immediacy is intoxicating and enchanting. You’re close to the elemental forces, bare and raw.

The American version of the book is even printed in a beautiful blue-green ink to reflect some shade of this landscape—the northern lights, glacial blues, moss or lichen.

Katy: Icelanders seem to find and invent stories about the natural landscape.

Kendra: In Iceland, I feel like the more time I spend on the landscape, the more I think about how this landscape impacts the way you think. Having to trust what is and isn’t there. The mist blows through, and you lose the land. Above you, if only it is dark enough and the clouds pass for you to witness, the Northern Lights. We as humans make things of what we can’t see through things we can see, and back again.

Katy: In the book, you write that a particularly Icelandic problem is how to display what can’t be seen. In the Icelandic Sea Monster Museum, were you convinced by the 4,000-plus testimonials housed there?

Kendra: The museum doesn’t have an atmosphere of trying to convince you. As an essayist, I’m concerned with tracking things down and figuring things out. But I’m often much less interested about the facts of what happened than the facts of the stories we tell and latch onto and propel forward. The stories are getting at something we need to talk about. I’m less interested in the question “are there sea monsters?” and more interested in why we talk about them.

Katy: I’m curious about why you chose to talk about certain museums and private collections, and not others.

Kendra: I could have written about every single museum in Iceland—you could make a point of visiting them all in less than a year—but then you’d be missing a lot by making the priority of covering the board. I didn’t want to just talk about the places you could go, but the depth of what has happened at these places.

The Skógar Museum was the second museum in Iceland, and now there are nearly 300 museums—most of which cropped up in the 1990s or later. The lives of that generation of collectors span a shift in the independence of the country. [Iceland became independent from Denmark in 1944]. Their lives span widely different economic fortunes and possibilities, and I think sharp change might precipitate and cause collections to endure because you have such awareness of the thing you’re about to lose, the thing you’re going to forget.

In the heart of Reykjavík, a punk rock museum opened in 2016 in a former underground public toilet. It didn’t exist when I started my research in 2011. You could ask at some point, how many museums do we need? How many can we support? The need for museums will not dissipate, but now we’re moving from an era of trying to hold onto things to an era of trying to let things go.

Katy: When you place something in a collection, you’re often placing ownership over it—holding onto it personally or institutionally—but I didn’t get that feeling with Petra. She didn’t call the Icelandic stones hers, but everyone’s. Soon tourists were coming to her house to view the collection (even complaining about there being only one bathroom).

I’m taken with the idea of the private becoming public. The very act of writing is a private thing made public. In the book, you say that you come to Iceland “because of the borders of this place. Because not just here but always, something happens at the edges.”

Kendra: One of the first things that struck me in Iceland was this malleability. I kept noticing this pattern: the tipping of a private collection like Petra’s becoming a museum. On my second trip to Iceland, on my way to the airport with the daughter of the founder of the Phallological Museum, she pointed out Icelanders use one word for collection and museum; there is no border there to cross.

It makes me wonder if a similar lack of distinction exists between public and private, too. The phrase the Icelanders always use is, “We are so few.” Iceland is a place where the fact that people have survived here for a thousand years is no small feat. You have to assume that knowing your neighbors is part of that survival. Having information shared and passed on is critical.

Also, in Iceland you don’t have one thing that defines you, but maybe six different roles. If you know you have that flexibility, you might naturally see borders as less rigid. Take the crime writer Yrsa Sigurðardóttir, who works as a civil engineer. She was out on some remote project and started writing because she got bored. She manages to publish a book a year without, I’m told, having to give up the day job she loves.

Katy: I’ve read that Iceland has the most authors and readers per capital of any country.

Kendra: Literacy rates are among the highest in the world, and they say one in ten Icelanders will publish a book in their lifetime. Þórður Tómasson of the Skógar Museum was writing a book when he passed (January 2022). He’d written 26 books by the time I met him a couple of years ago. There are books that make me want to become a translator—one documents every polar bear landing on record in Iceland—and one Tómasson wrote about words for Icelandic weather. Before his book existed, one Icelander wouldn’t have known all these words, they’re so regionally specific. For example, the south is windy in a way that it isn’t anywhere else.

Katy: That reminds me of a book, Fifty Words for Snow, by Nancy Campbell. Snow means something different to different people because of where they are. Place makes its mark on language.

Kendra: Always, but sometimes it’s hard to see.

Katy: How do you see the act of traveling alongside collecting?

Kendra: Both are actions of expansion, of possibility. I enjoy the collectors who are good at amassing variation, who attend to how “this is slightly different from that.” You can see the knowledge gained through repetition and through variation.

Katy: And did that idea of alternating repetition and variation help you to organize your book in a way?

Kendra: I love structure. The book is organized by the long essays. I thought of them as pillars and wanted each to stand alone and hold something up. The chapters are sequenced to move you from the individual to the group, from the tangible to the intangible, from the thing to the story.

And still I like the interchangeableness, how you can walk through the book to the thing that draws your attention, exactly like you would in a museum. I feel like Petra is the heart of the book, but that’s not where we start.

Katy: Can you tell me about an unexpected moment you experienced while researching this book?

Kendra: I remember going down into the national library’s map collection with a librarian whose name means a mountain covered with snow in Icelandic. The librarian said that maps are made by outsiders. I would have thought that one would need to know a place to make the map, but his point was that if you know a place you don’t need a map. This official defining record of a place is made by other people trying to make sense of it.

Katy: And as an outsider, you are perhaps thinking about Iceland in ways that Icelanders do not or cannot.

Kendra: Several Icelanders told me they were interested in reading my book because they have curiosity about how the world sees them.

Katy: How do you see them?

Kendra: I relied a lot on the kindness of Icelanders, on being invited in. The best interviews I did in Iceland had someone sitting in as translator. It slows things down, and many good things happen when you slow down. The translator was usually a friend or neighbor who’d say, “oh, you should tell her about that other thing.”

Something that doesn’t make it into the book is a napkin collector on the Island of Heimaey, Eygló Ingólfsdottir. Napkin collecting strikes me as a particularly Icelandic practice. Napkins are mass-produced but in such variety. They change over time and tell this story about graphic design, baptisms and weddings, different social groups getting together. I have this vision of a group of kids trading napkins like baseball cards.

Eygló Ingólfsdottir and I had our interview at her kitchen table. A fair number of the most memorable interviews were at kitchen tables, often over waffles with rhubarb jam just coming off the stove. There’s maybe no more holy act than having someone invite you to their kitchen table to tell you their story.

Photo by Nan Coulter

Photo by Nan Coulter